Picture this: jagged mountains in the distance, dry desert stretching for miles, and that deep, electric blue sky you only get when you’re way up high. That’s the backdrop—both literal and emotional—for Chloe West’s paintings. Her work is a curious fusion: old-world Dutch iconography meets the gritty, myth-soaked Americana of the Wild West. It’s like Rembrandt saddled up and rode into Wyoming.

West didn’t just study the West—she is the West. Born and raised in Wyoming, she grew up with peaks on the horizon and prairie in her bones. And it shows. Her hyperrealistic portraits and tableaux don’t just depict a place; they live and breathe it. In her solo exhibition Games of Chance at HARPER’S, she draws deeply from the well of European portraiture and still life—but spins it with something more personal, even rebellious. These are stories told through her own face, her own hands.

One painting, Cowboy Philosopher, is a showstopper. West sits at a table, dead-on stare, no pretense. Beside her? A mountain lion skull. The table’s draped in a celestial cloth, echoing the kind of mystical seriousness you’d see in a 17th-century Flemish study—think Koninck’s A Philosopher, only it’s not an old man with a beard, but a modern woman staring you down like she knows something you don’t. And maybe she does.

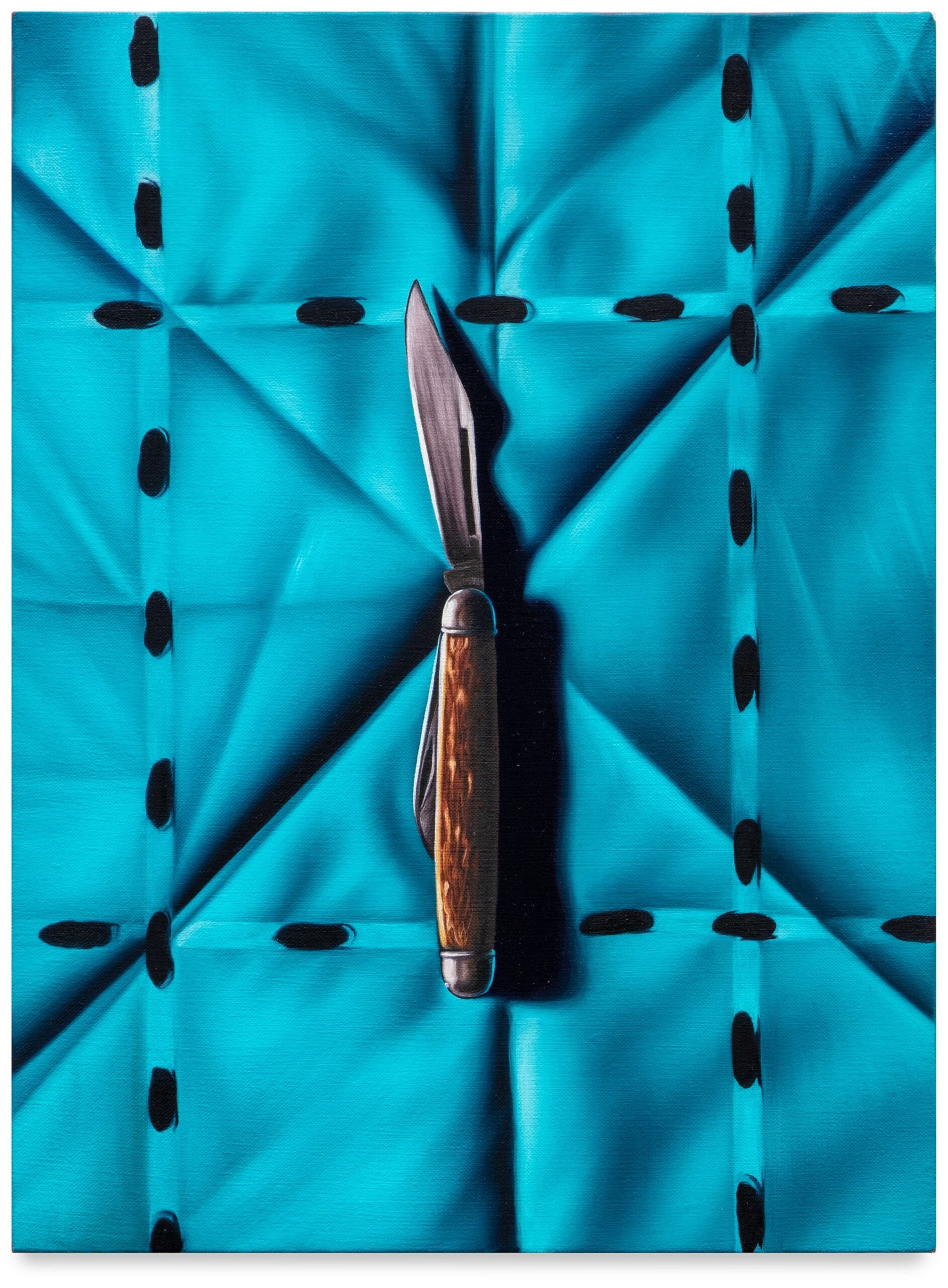

“Trapper’s Still Life” (2024-5), oil on linen, 48 x 38 inches

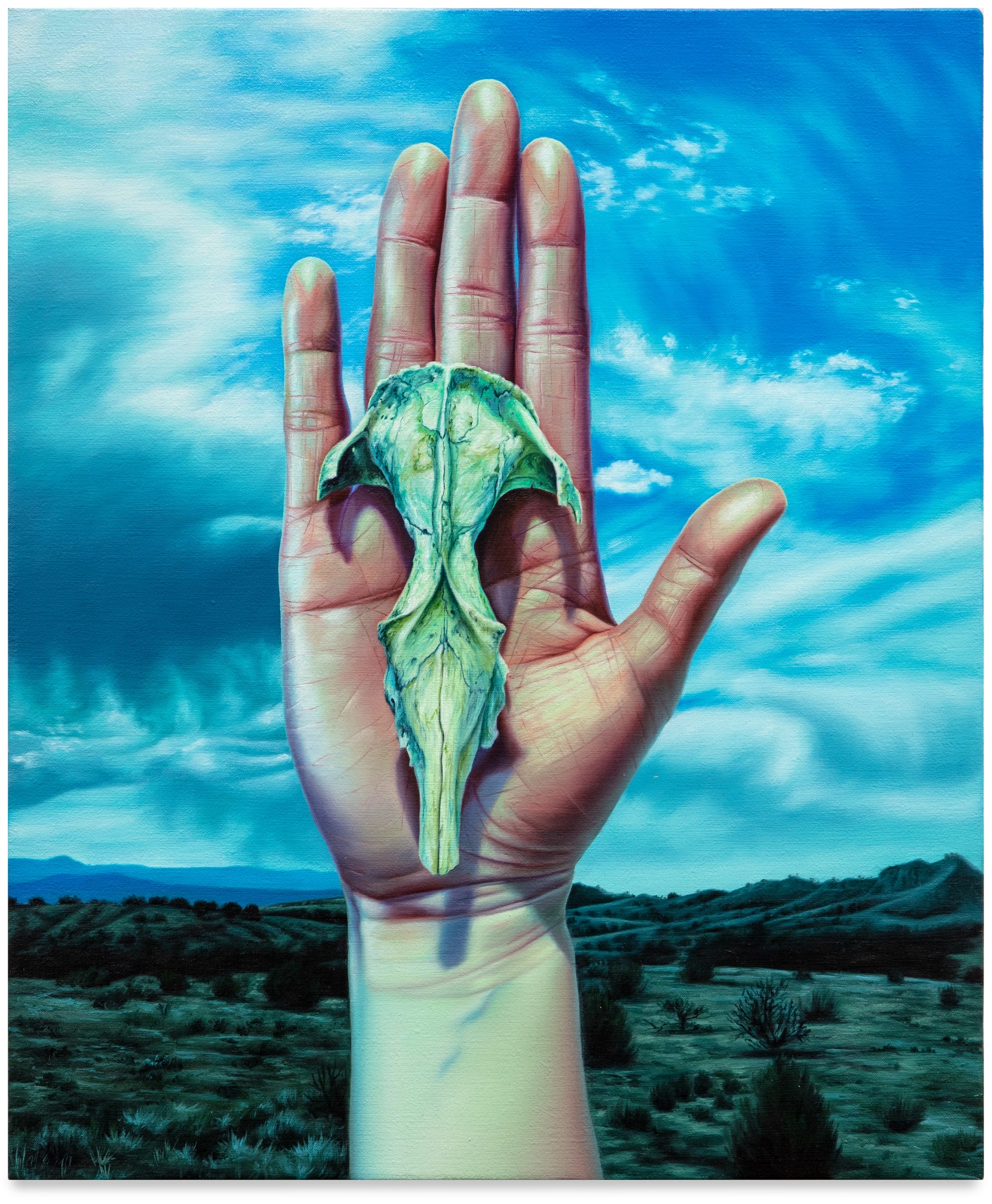

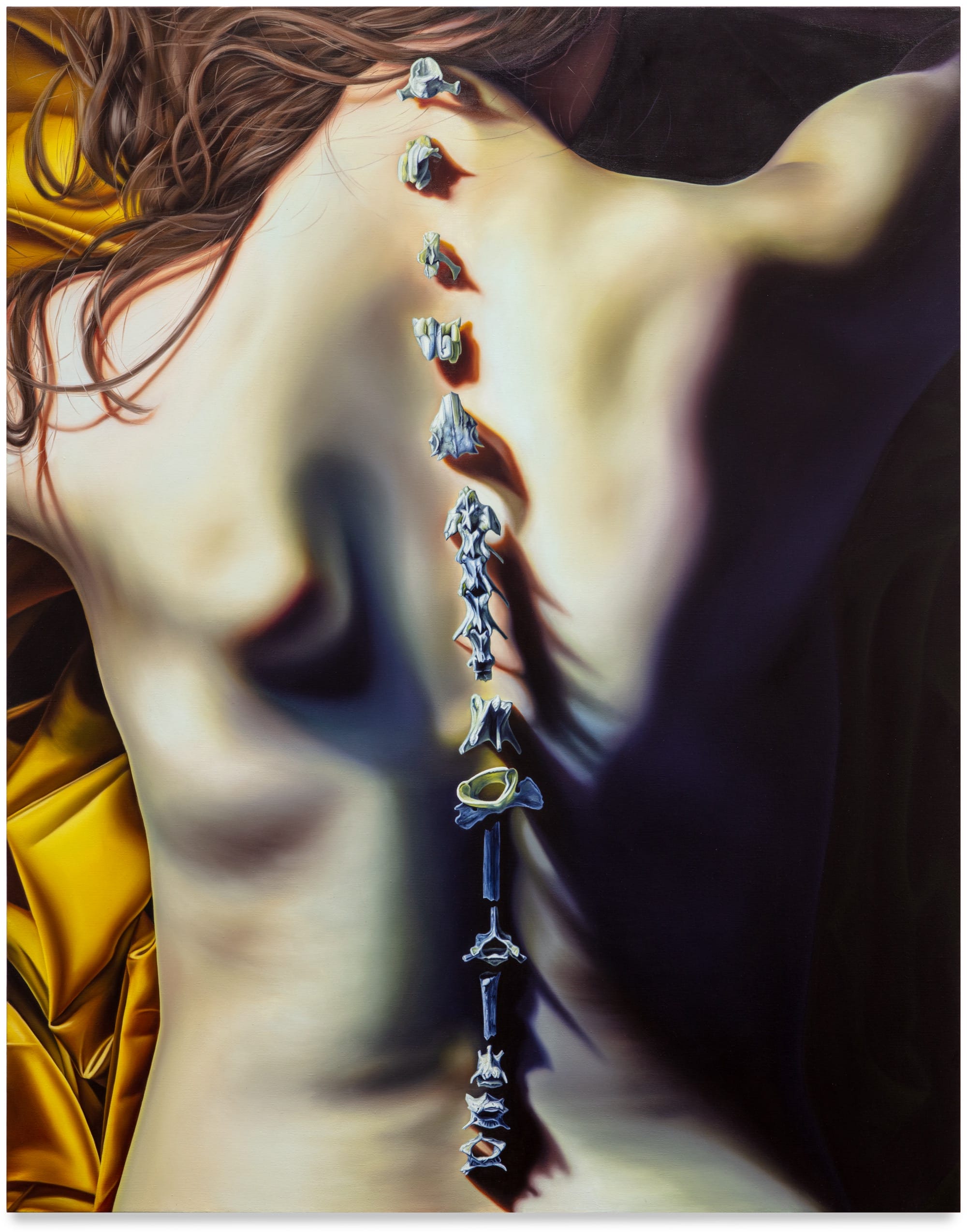

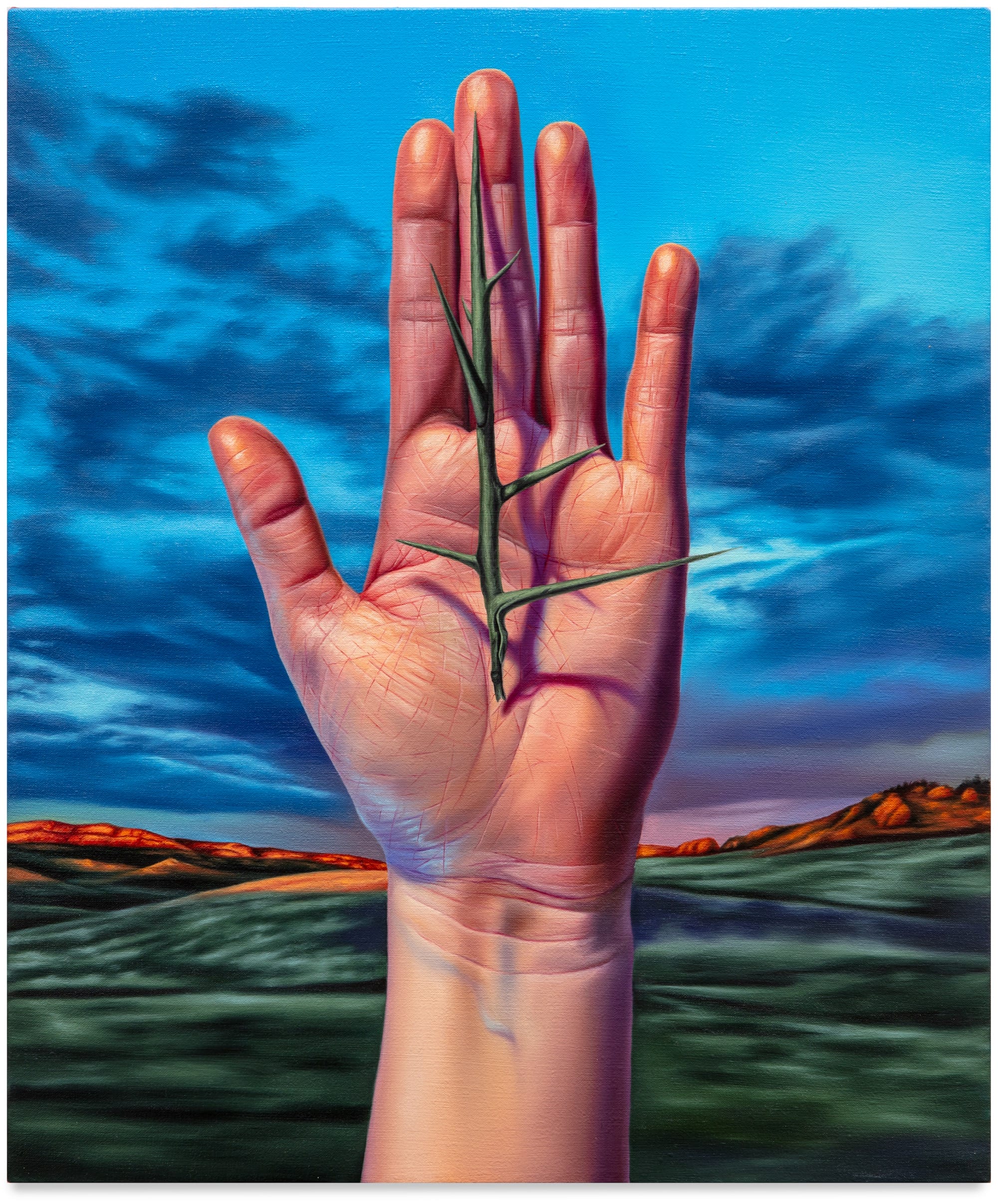

West plays with symbols like a magician with a deck of cards. She places her own body in these scenes surrounded by bones, knives, fabric, and light that cuts like a blade. The effect is haunting. Beautiful, but haunting. It’s memento mori with a side of folklore and just enough danger to make you lean in. The bones, the thorns—they’re not just gothic props; they’re reminders. Life ends. Stories loop. Time bends. And in the West, the sun doesn’t just shine—it exposes.

She dresses in western gear not as a costume, but as a continuation—almost like she’s entering the myth instead of just commenting on it. There’s something defiant in that. She nods to the old stories—Manifest Destiny, frontier grit—but then turns them inside out. What if the cowboy wasn’t a man? What if the wilderness wasn’t tamed but remembered?

Throughout Games of Chance, West doesn’t just paint pretty pictures. She rewrites the rules. She challenges the romanticism of frontier heroism, chips away at the hyper-masculine ideal, and suggests a different legacy—one that’s more complicated, more personal, and infinitely more real.

The show opens today in New York City and runs through May 10. If you’re even remotely curious about the power of portraiture—or the many lives of the West—it’s worth seeing. You can dig deeper into her work on her website or Instagram.

And there’s one image I can’t get out of my head: a woman’s hand, steady and pale, holding an opossum skull. Behind her, a stormy Western sky brews in the distance. It’s beautiful. It’s eerie. And it’s so very Chloe West.

“Portrait with Capped Skull” (2024-25), oil on linen, 58 x 48 inches

“St. Veronica at the Geyser Basin” (2024-25, oil on linen, 48 x 38 inches