For Anna Ortiz, the borderlands aren’t just geographic—they’re deeply personal, a kind of threshold where memory, myth, and identity all blur together. Though she was raised in the factory-lined streets of Worcester, Massachusetts, her roots stretch deep into the soil of Guadalajara, where her family lives and where her creative journey quietly began.

Trips back to Mexico weren’t just family visits—they were something closer to pilgrimages. In those visits, Ortiz absorbed more than language and scenery; she inherited a legacy. Her grandfather painted faces with reverence. Her aunt shaped sculptures that felt like they held stories inside. Being around them was like being let in on a family secret: art wasn’t just something you made—it was something you carried.

That push and pull between two worlds—New England’s reserved stillness and Guadalajara’s vivid pulse—has followed her into adulthood. It lingers in her work, echoing in colors, forms, and the surreal spaces she constructs on canvas. In Prophecy Here and Gone, her upcoming solo show at Mindy Solomon Gallery, Ortiz invites us into a world where time floats unanchored, where ancient histories hum beneath the surface.

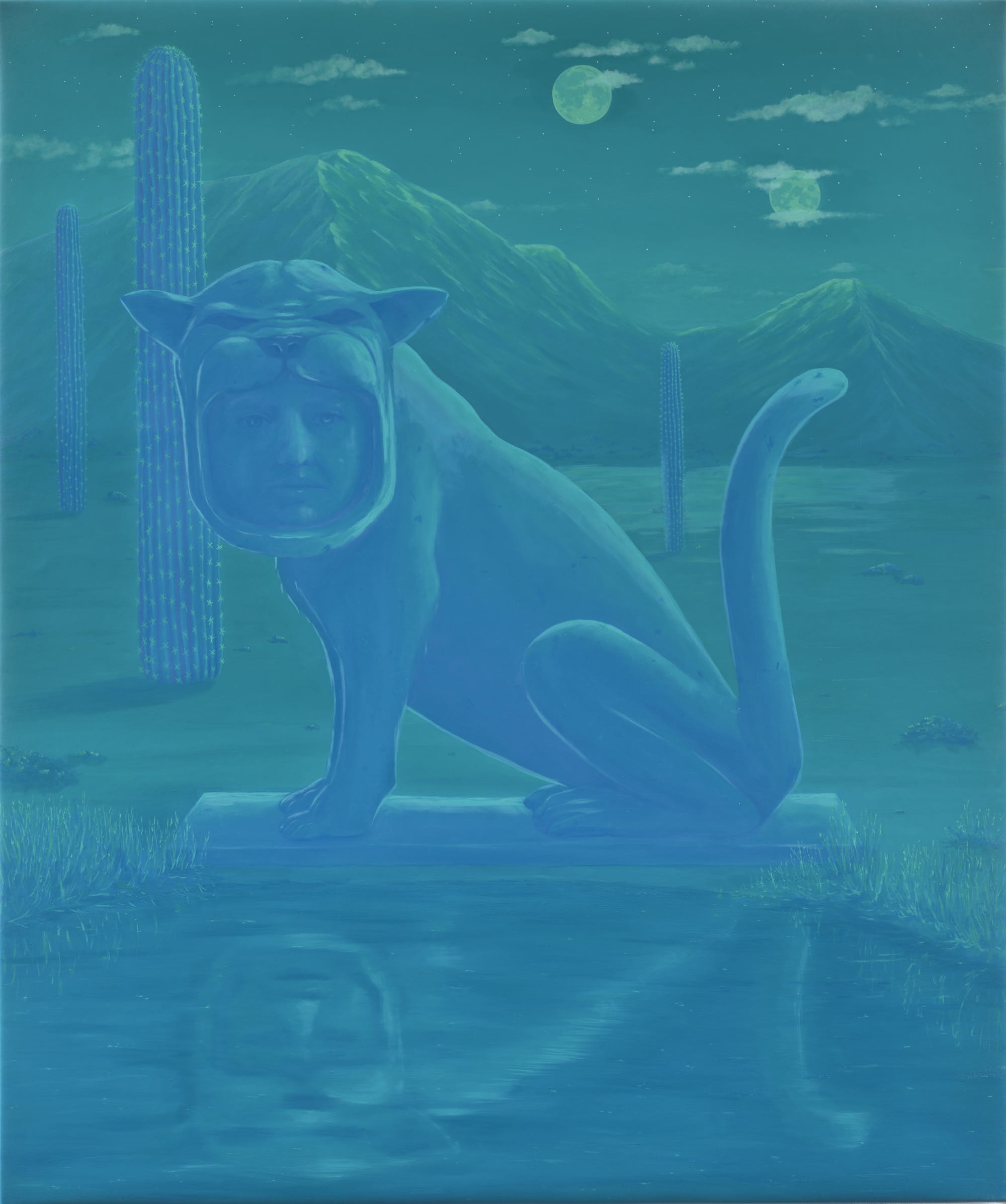

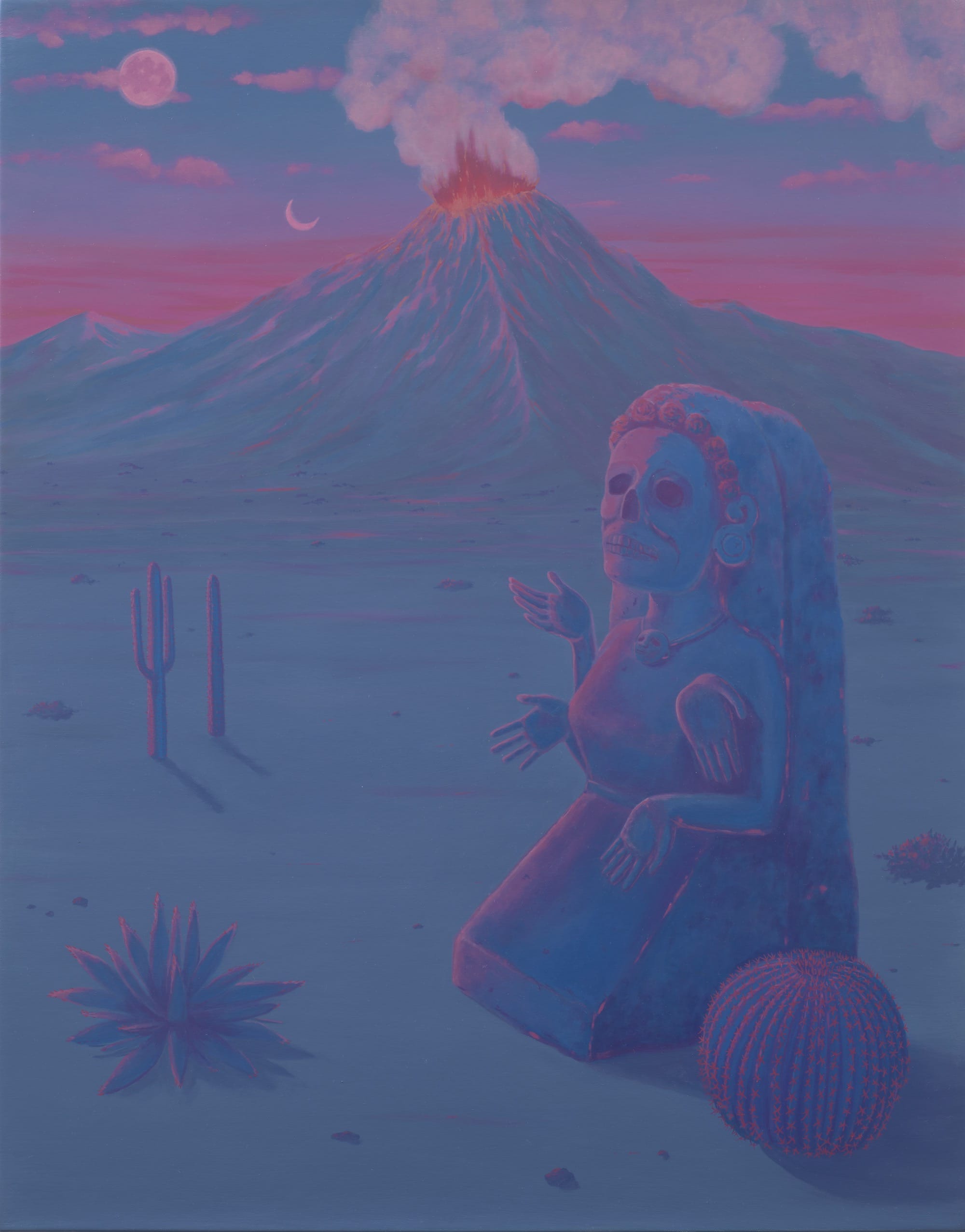

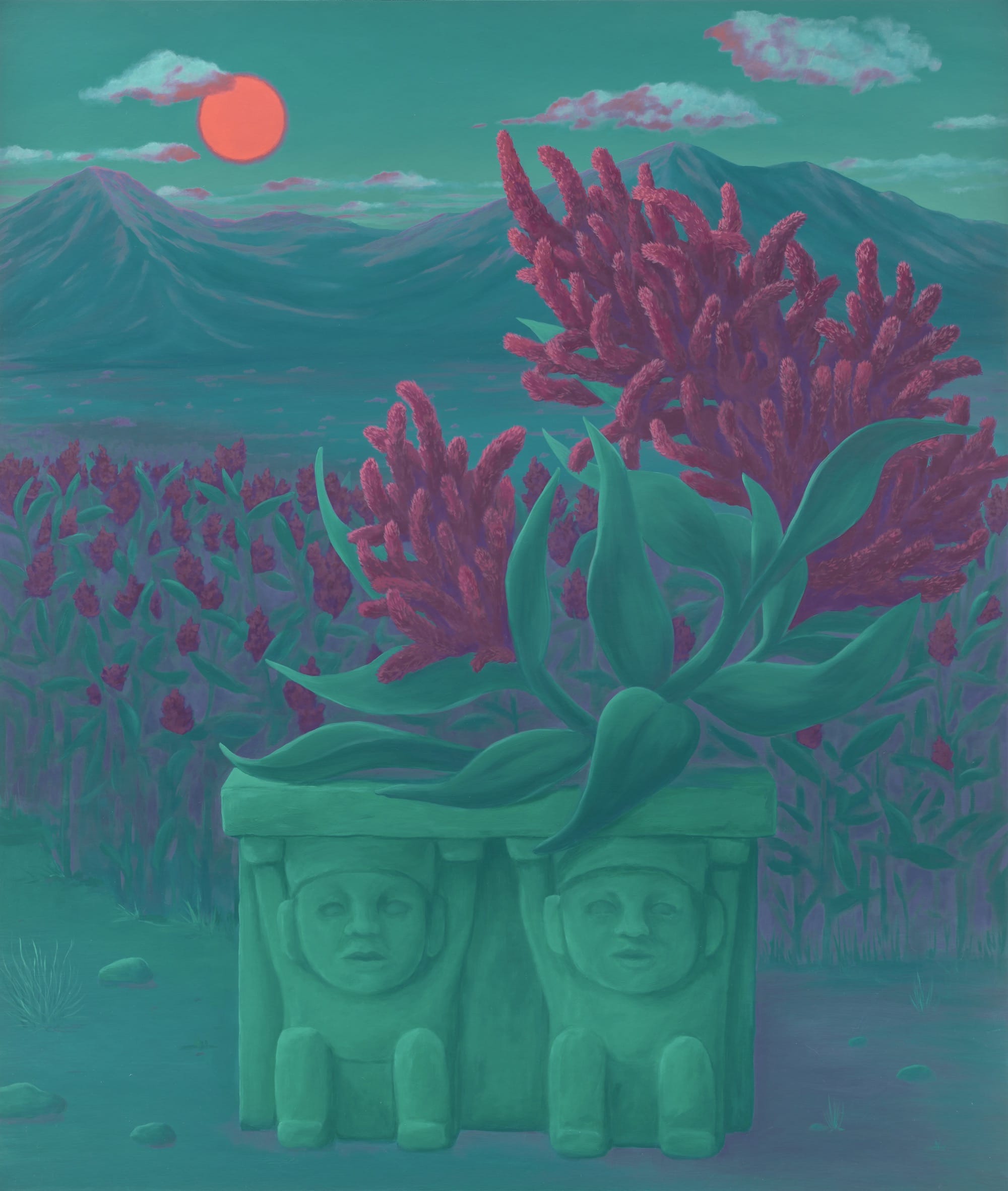

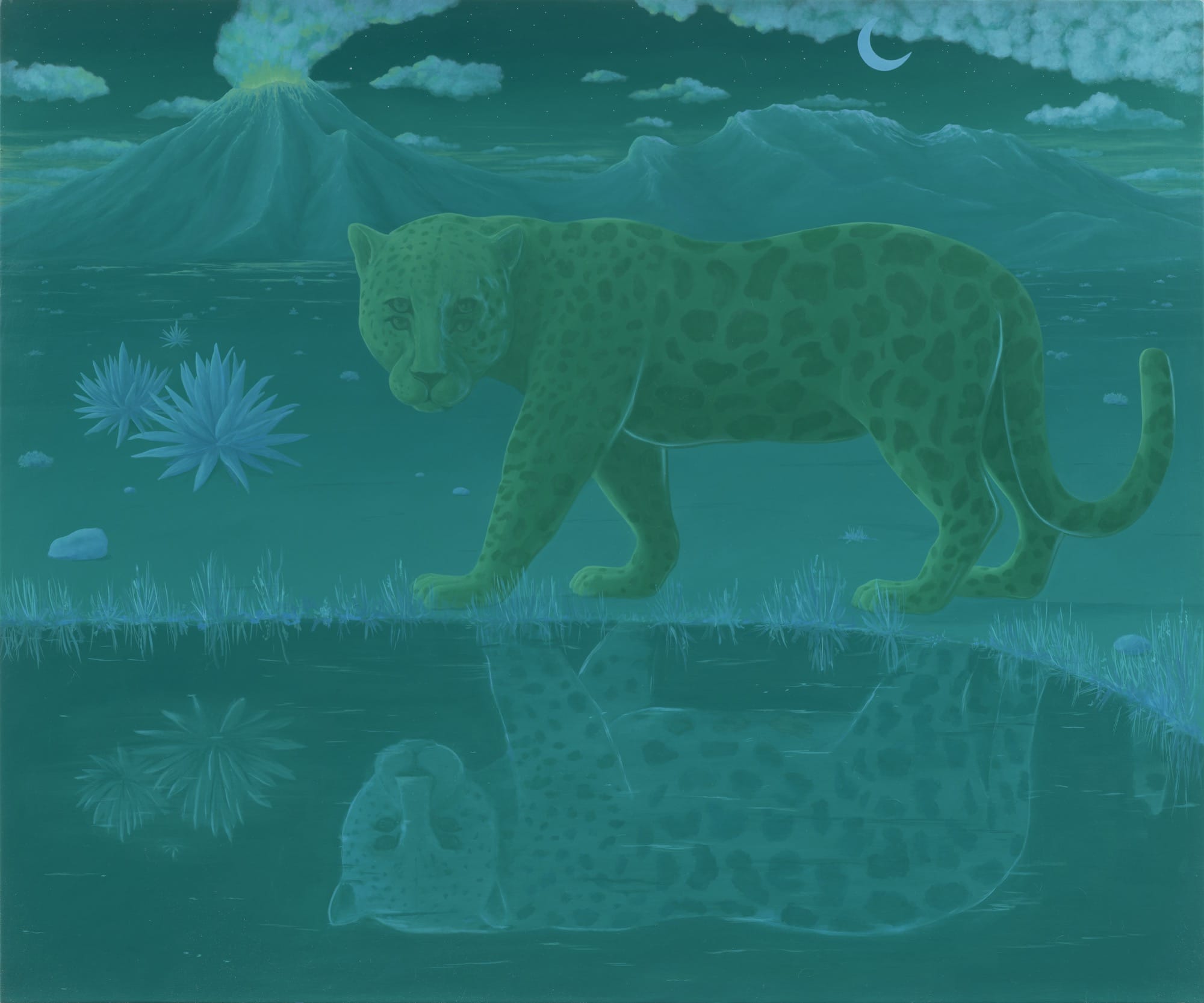

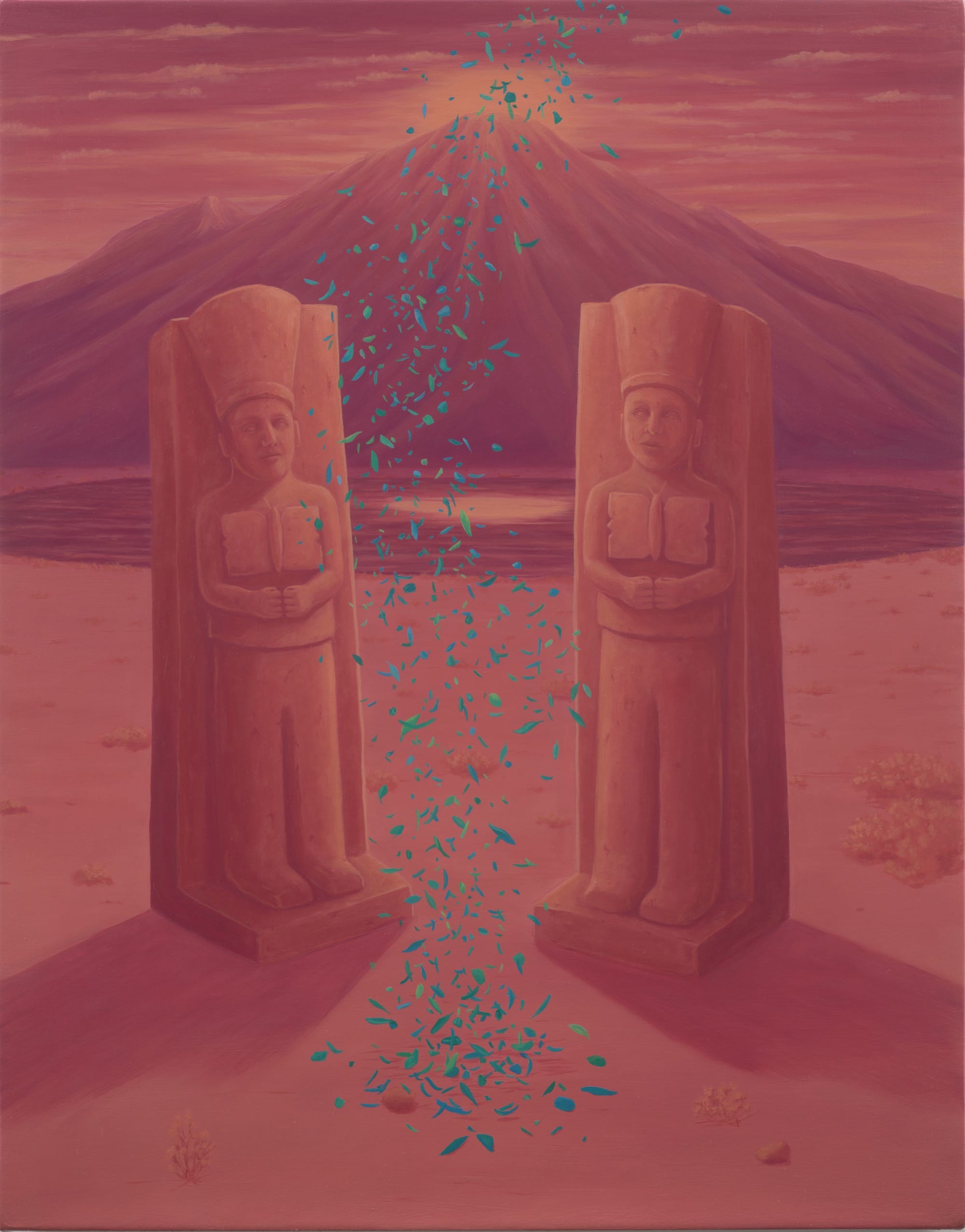

Her color palette leans into the dreamlike: vivid pinks, blues, and greens that feel lifted from a fever dream or the glow of a desert just before dusk. These paintings don’t just reference Aztec history—they resurrect it, allowing myth and memory to share the same visual space.

One standout piece, Al Otro Lado de Texcoco, offers a view into a lake nestled beneath La Malinche, framed by a thicket of cactus. Historically, this was the lake that welcomed the Aztecs before it was drained by Spanish colonizers in a failed agricultural experiment. Ortiz doesn’t just recreate the landscape—she reimagines it, asking what it might have looked like had the land been left alone to speak for itself.

There’s a deep sense of duality throughout the work. Ortiz often paints in pairs—twin figures, mirrored animals, echoes of symmetry—not just for balance, but as a way to reflect on the paths we leave behind. “I think about unrealized lives,” she says. Pareja, for instance, features a pair of agaves standing like silent witnesses, while Tula depicts two towering sculptures, their butterfly-adorned chests calling back to Toltec ruins. Elsewhere, jaguars stare out from the canvas, their reflections rippling just beneath the surface, as if they too are straddling realities.

In many ways, Ortiz is building an alternate universe—one where the ancient past wasn’t interrupted, where prophecies came to pass differently. She’s fascinated by how civilization shapes nature, and vice versa, but her work is also quietly personal. “Loss is central to all of this,” she confesses. “I was once so fluent in Spanish, so immersed in my heritage. But because of things that happened in my family, I lost that closeness. I lost the language.”

Through her painting, she seems to be reclaiming what slipped away—not by recreating the past, but by imagining how it might have blossomed under different conditions. These aren’t just visions of what was—they’re portraits of what could have been. “These works are about the lives we didn’t get to live,” she says. “But I believe they still unfolded—just without us.”

Prophecy Here and Gone runs from April 5 through May 10 in Miami. You can explore more of Ortiz’s work on her website or follow her on Instagram.

“Al Otro Lado de Texcoco” (2025)