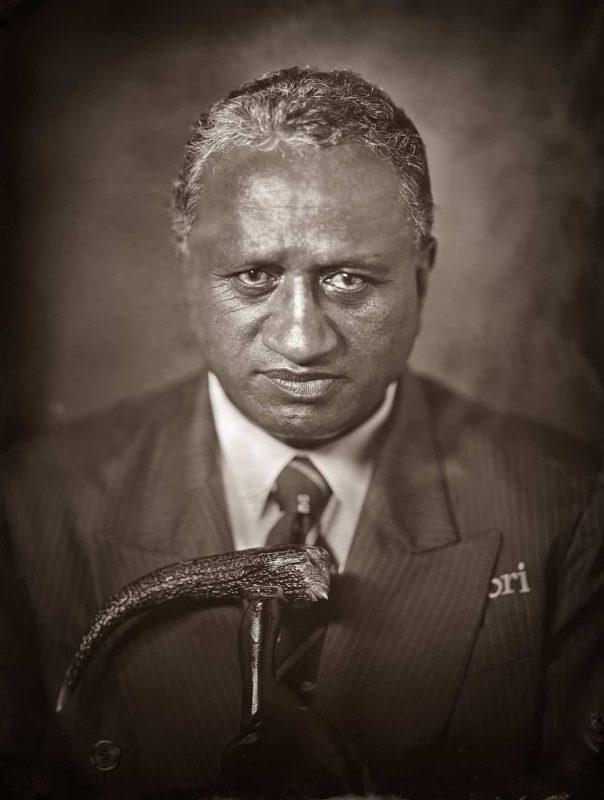

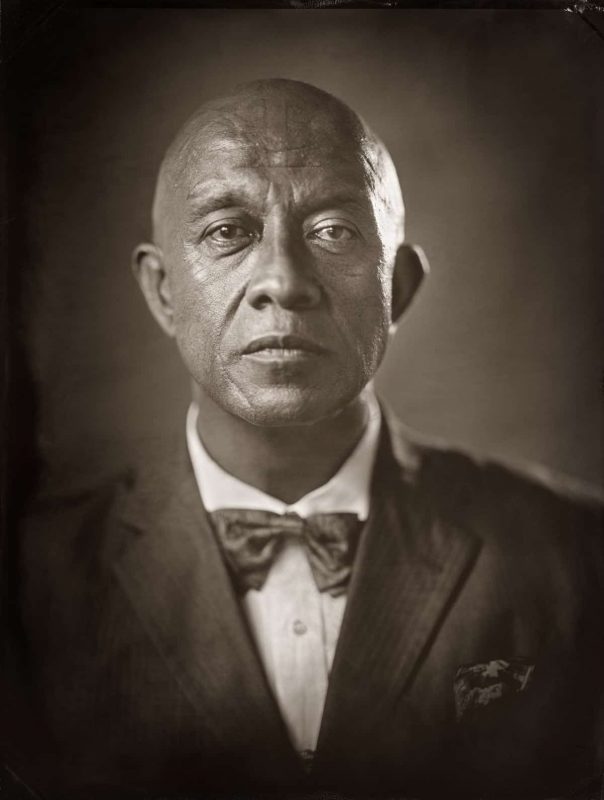

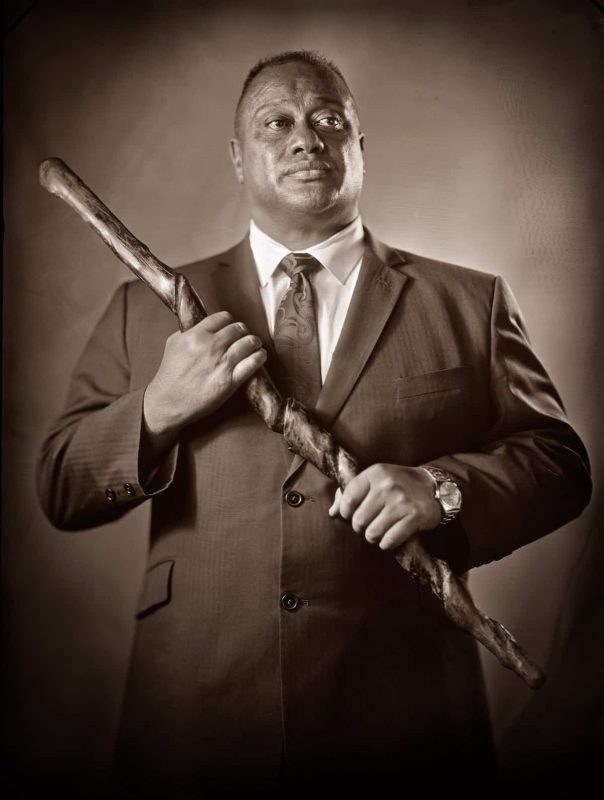

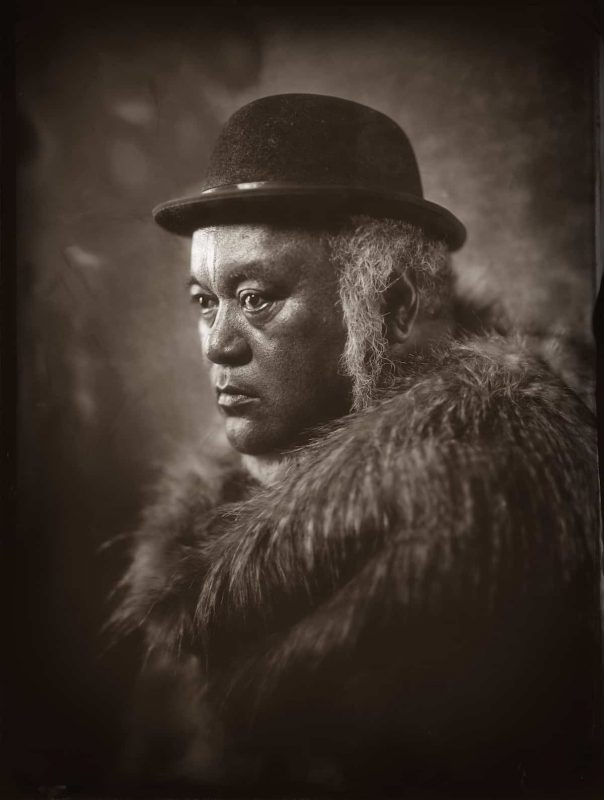

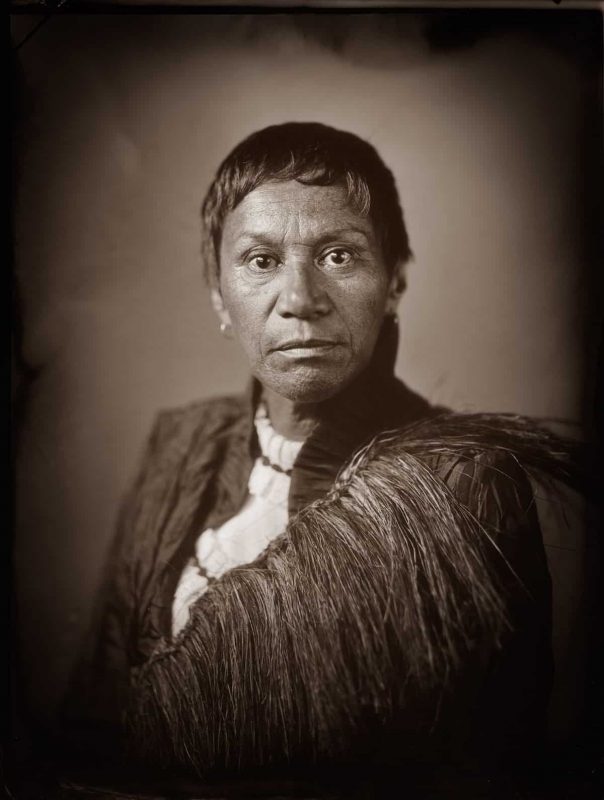

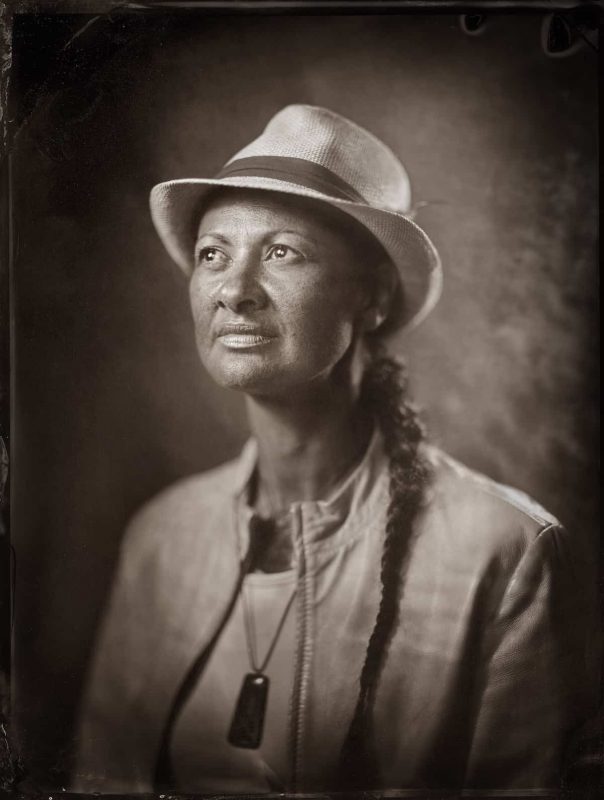

Influenced by wet plate portrait photography of the past, photojournalist Michael Bradley‘s Puaki is an observation of the Māori culture.

Specifically, Bradley investigates tā moko, the permanent markings on the body and face practiced by New Zealand‘s indigenous civilization. Together with his collection of gorgeous portraits, he recalls the near erasure of this significant cultural heritage.

Bradley, who has been practicing wet plate photography because 2013, first stumbled upon the idea for Puaki when considering damp plate pictures in which people’s tattoos often didn’t appear. This is a spark to investigate the background of tā moko and create the long-term job.

“In Māori civilization, it’s thought everyone has a tā moko beneath the skin, just waiting to be disclosed,” writes the Te Kōngahu Museum of Waitangi. “The difficulty is, when photographs of tā moko were originally taken in the 1850s, the antiques hardly showed up at all. The wet-plate exact method used by European settlers functioned to erase this cultural mark –and as the years went by, this proved accurate in real life, also. The ancient art of tā moko was suppressed as Māori were assimilated into the colonial world.”

Tā moko has witnessed a resurgence since the 1990s along with the pride every player takes in their mark is apparent in Bradley’s photographs. By comparing the digital and moist plate photographs, it is clear that tā isn’t only about private expression, but a cultural mark that is worn with dignity.

Puaki that means”to come forth, show itself, start out, emerge, disclose, to give testimony,” is Bradley’s way to plant a seed with the public. He expects they will learn more about tā moko and the way Māori culture forms an integral element of contemporary society. Practically erased from the pages of history, the practice is a demonstration of how cultural customs will continue to flourish in the modern era.

H/T mymodernmet