Art and fashion have shared canvas for centuries. Quite literally, the switch from wood to (up until then, mostly clothing material) canvas in the 15th Century as the primary material for painting allowed detailed portraiture. The great and the good of Renaissance Europe commissioned artists to display them in their finery. In the present day, we have fashion as high art – think Issey Miyake’s exhibitions in museums from Paris to Tokyo – to art as consumer fashion when we look at the Keith Haring Foundation licensing his works to Uniqlo and Jean Michel Basquiat’s dinosaurs becoming ubiquitous on kids’ t-shirts. These trends have not been met with universal approval.

Is sport art? It can be. We can look at the movie Zidane: A 21st Century Portrait, which tracks the French footballer across the 90 minutes of a game. Soundtracked by post-rockers Mogwai, it’s an excellent illustration of how sport can convey drama outside the well-trodden film board of portraying it in documentary format. Likewise, we can look at the iconic stills of Muhammad Ali, whether it’s the Neil Leifer shot of Cassius Clay snarling over the downed Sonny Liston or the extensive collection of sketches by LeRoy Neiman that now take pride of place in the Muhammad Ali Center in Louisville.

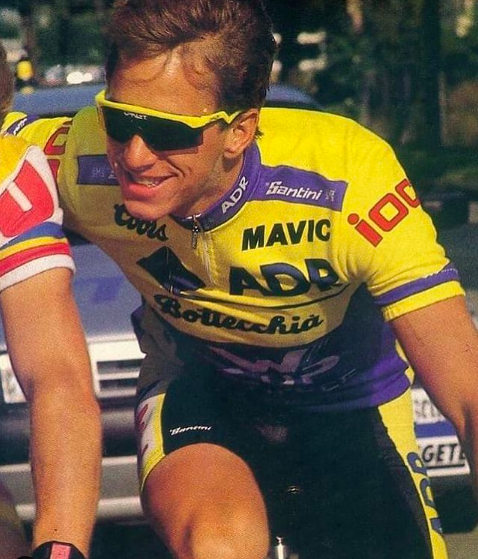

It’s in this vein that the optical brand Oakley has inserted themselves. Initially eschewing ideas of sunglasses as fashion statements, they’ve produced pieces for athletes since their move into eyewear in the 1980s. While in that time, they were certainly part of some iconic moments – Greg Lemond thundering through Paris in Oakley sunglasses to be the first American to take the Tour de France springs to mind – it’d be a stretch to call them conscious art. However, in 1994, that changed.

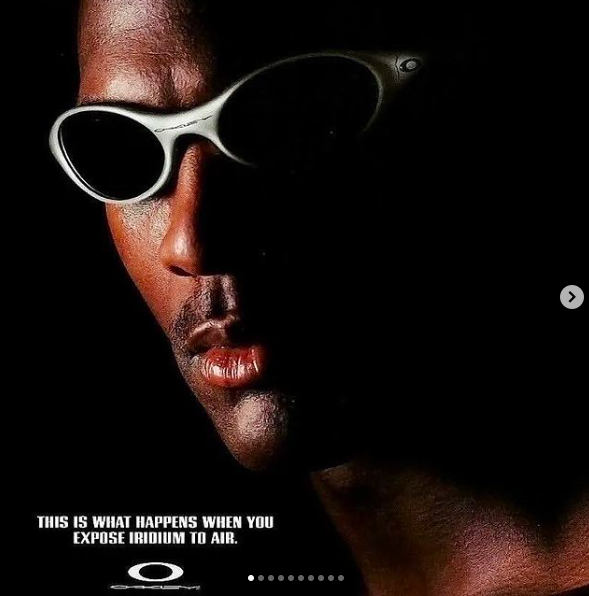

Oakley’s print ad campaigns had, until then, been technical. You’d have pictures of various frames and lenses and a spec sheet of how they’d outperform the competitor. The 1994’s new Eye Jacket models ad campaign featured a simple portrait of a yet-to-be-GOAT Michael Jordan in the shades. The stark image of an emotionless 23 against a black background could’ve been mistaken for a model’s headshot. There’s no physical drama, as there is in the famous ‘Jumpman’ logo that adorned his Nike signatures, only the contrast of the glasses against the face. Jordan is impenetrable, the shot almost anti-Annie Liebowitz. Rather than updating a classical portrait, a la the French artist Kyès, the effect is one of hypermodernity; it still looks futuristic nearly three decades on.

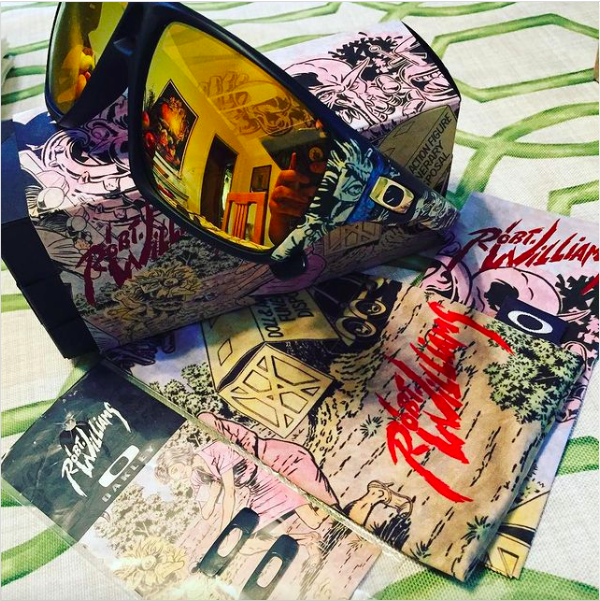

From there, Oakley has moved more formally into art. 2006 saw the launch of the Artist Series, with the initial piece being a limited edition of 100 Gascans featuring artwork from L.A. street artist David Flores. Having initially been acclaimed for his Giants series of paintings in San Francisco and Icons in NYC, Flores has collaborated with the likes of the DFisXL gallery in Tokyo and had his Kidrobot toy Bad Dunny enshrined in the Museum Of Modern Art. The clairvoyant connection to KidRobot continued with a Frank Kozik pair of the Hijinx model in 2008. The series rounded off in 2012 with Dispatch models styled by the most highbrow of “low-brow” artists, Robert Williams.

The move into art took Oakley off the track and onto the catwalks. A 2018 collaboration with Vetements saw Demna Gvasalia make fearsome spiked alterations to a series of frames; their resale market is now equally as fierce, with prices north of £5000 being commonly asked.

It hasn’t stopped there. 2020 saw the release of the Kokoro Collection in partnership with Meguru Yamaguchi. Moving on from having an artist pick a certain model, Oakley handed the full line to the Japanese disruptor (currently resident in Brooklyn), which resulted in 11 pieces being produced and, this time, mass-marketed. The models included nods to his native land with the Radarlock Asia Fit and Radarlock Asia Fit; however, Yamaguchi also included the classic Holbrook and Frogskins in the line. Ever the innovators, Oakley ensured each item in the range was unique, with each piece undergoing a specialized spin technique using a custom-built machine that aped Meguru’s signature brushstrokes. The collection was forecast to celebrate an event that never happened: the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Undeterred, Oakley pressed on and released them anyway.

The Steampunk movement has revitalised the idea of wearable art in recent years (in which some of Oakley’s frame shapes are clearly influenced). Fashion picks, chooses, and evolves. If there’s an uneasy relationship between high art and fast fashion, perhaps brands like Oakley – by being responsible custodians – can bridge the gap.